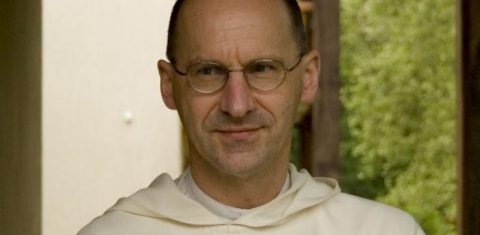

The meeting set off with Father Michał Paluch OP, rector of Angelicum, the Papal University of St Thomas Aquinas in Rome. He began by giving tribute to this cycle of debates on solidarity, it being a huge concept for societal change that began some forty years ago in Poland. He then defined solidarity according to the encyclical Sollicitudo rei Socialis announced at a crucial moment in 1987 several years after events that set the ball rolling for the Solidarity movement in Poland which took place before the Polish Round Table Agreement and the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Father Paluch quoted from this encyclical ‘Solidarity isn’t just a vaguely defined empathy nor a facetious pulling of the heartstrings at the sight of hardship for many, be they close to us or far from us. Rather, it is the strong and lasting will of involvement at the group level for us all, that being the good of all as well as each person since truly we are all responsible for our collective good’.

The Dominican here emphasised inclusiveness tied into this definition. After which he cited words of John Paul II from during his pilgrimage to Poland in 1987 ‘We all carry each other’s burdens – this pithy statement of the apostle is an inspiration for solidarity on the social and human level. Solidarity, hence indicating one together with another, and burden carried together collectively and communally. Never one against the other, and never the burden being carried by one person without help of the rest, for the struggle must not be something greater than solidarity itself, so as to overburden it.’

With these words Father Paluch finds retreat from a reality of social divides and class divides, to a reality of mutual respect for one another and cooperation with one another. The Pope defined solidarity as an imperative for achieving collective good, a conception which makes no room for abusive force. Father Paluch added that this notion is still very universal and likewise relevant. But nevertheless it somehow still proves to be beyond our reach and this Father Paluch explains as a result of us focusing on the notion itself and not paying due attention to the course that leads to its fulfilment. Just as a bodybuilder can overstretch his mark injuring himself unintentionally with too heavy a weight, so we can overstretch ourselves when not prepared adequately for the aims and challenges set out in front of us.

Father Paluch notices how it would presently seem that achieving a world that is fitting for everybody one would have to minimise one’s own sense of personal identity, so as to regard and respect others not in reference to who we are, but aside from this. In turn this may cause a person to focus too much, even entirely, on himself in considering his own identity at the cost of the good of other people. Father Paluch finished by mentioning that ‘without the ability to fully realise our identity by not taking into account the religious dimension, we won’t have the necessary disposition for undertaking the great aims and ideals for social justness and reducing social inequalities in our societies’.

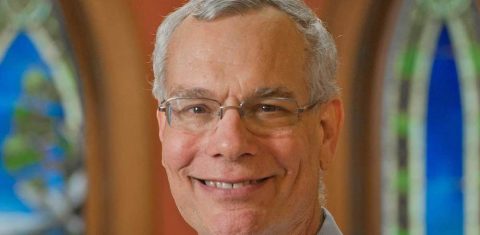

The next to speak was Dr Austen Ivereigh, a biographer, who worked with Pope Francis on his book Let Us Dream: The Path To A Better Future published in December 2020. He focused on the way solidarity is conceptualised in the teachings of Pope Francis. The book ‘Let Us Dream’ happens to be the first book of our current Pope which provides an answer to the events currently taking place as a result of the pandemic and the crisis that has ensued. In his book the Pope supports the assertion that the pandemic will unchangeably influence the face of human societies, as is with every crisis providing opportunity for self-reflection. Dr Ivereigh posed the question of why certain key moments change the world for a better place, yet others leave us no conclusions on which to build thereby leaving the world in a worse state.

According to Ivereigh, the Pope in his book shows that it is high time to build societies on the values of fraternity and solidarity, as opposed to relying on almost mythicised ideals of sovereign states. Pope Francis moreover questions how such a world could look if we actively implemented this kind of approach. According to the Pope, one of the key elements of such a new order would be an economy that gives access to work, to the earth’s resources, while taking care of the planet. This kind of an economy would require a change in politics that would gear economic aims differently to what is currently being demanded. Dr Ivereigh pointed out how in Let Us Dream the Pope exhorts us not let opportunities of this current crisis pass by for serving others and initiate movements which uphold the dignity of the human being as the forefront.

The next speaker was Sally J. Scholz from the University of Villanova. She pointed to how Pope Francis’s social teachings bring an innovative light to the notion of solidarity. First of all, she brought attention to the interdependency of solidarity and social justness. Solidarity requires justness in all areas, as inequality in one will lead to further inequalities, which can be seen currently with social justice movements. The next observation which Sally J Scholz enlightened us with, was how solidarity demands inclusiveness that comes with justness. Being a philosopher, she also appreciated that her definitions could be taken as being opposed to others, and thereby limit posited claims of solidarity in this respect, and further explained how this may prove in itself to be counter to the central ideals of solidarity.

Solidarity requires justness in all areas, as inequality in one will lead to further inequalities, which can be seen currently with social justice movements.

Another interrelated trope, Sally J. Scholz identified as the reciprocal nature of the workings of equality on solidarity, in that equality somewhat qualifies solidarity. The willingness to risk which comes with carrying each other’s burdens, exposes us to more potential hardships often unexpected. Yet, as the philosopher Sally J. Scholz here notes, greater quality and partaking in commonality together, not only brings with it greater risk, but furthermore an equal sharing of this risk between all involved. Scholz finished her reflection here with the observation that we are only humans at the end of the day who are fallen from grace and do still continue to fall, yet this gives opportunity to take responsibility for our imperfections and draw lessons from them, which is indeed an integral part of the recipe of carrying each other’s burdens.

The last of our speakers was Prof Tomasz Żyro from Warsaw University, who is also associated with Teologia Polityczna. He began his remarks by commenting on Solidarity as a social movement. Being a political scientist, the professor here noted that it was the words of John Paul II which initiated a new wave and awakening, since at once they gave fresh new wind to gaining freedom, while also being the starting point in building towards it. The year 1989 has been noted as Annus Mirabillis meaning wonderful year, and this critical turning point is well considered alongside historical analogies no less than the French Revolution which Prof Żyro explained brought down absolutism in the same manner that Solidarity brought down communism.

The Solidarity revolution has come to be regarded as an startling testament of human resolve for starting all over again and beginning anew. And it is such a testament according to Żyro, which finds parallels in the present social crises which we are living out as a result of the pandemic. Prof Żyro further underlined the aspect to be considered that of the divinity of the human being, where equality as regards to a person is closely tied to their dignity as a human being and likewise to their human rights. In his remarks Prof Żyro highlighted that the notion of solidarity finds particular resonance and significance within the context of today’s present crises. What is needed are societal changes carried out on a bedrock of solidarity with regard for the dignity of the human being, and furthermore that this doesn’t remain forgotten but rather takes on greater weight and meaning in the 21st century.

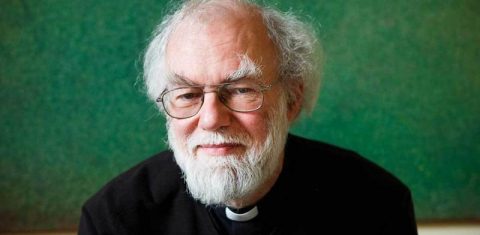

Lord Alderdice finished our meeting and debate on the point that we currently find ourselves in a rather curious moment. After all, forty years ago Solidarity was a movement that brought down existing structures in order to be able to build anew, whereas today we face a crisis which brings down human lives, relations and economies. It’s not a revolution leaving ruin in its wake as was forty years ago, but a crisis. The young as well as older people, do not see a clear horizon ahead of them to take hold of, rather they distrust politicians, economists even entrepreneurs alike.

So the question that resulted from our discussion sounded thus: do we have leaders as well as a vision of how to proceed with a new movement by putting solidarity at the core of all postulated here? Lord Alderdice does see hope in Christian communities and other religions, likewise in non-religious communities who rely on an authentic approach to humanity and human dignity. He elucidated that determination, inspiration and vision are key in taking us forward from the place and situation we currently find ourselves in.

Summary: Tomasz Sosnowski