- This event has passed.

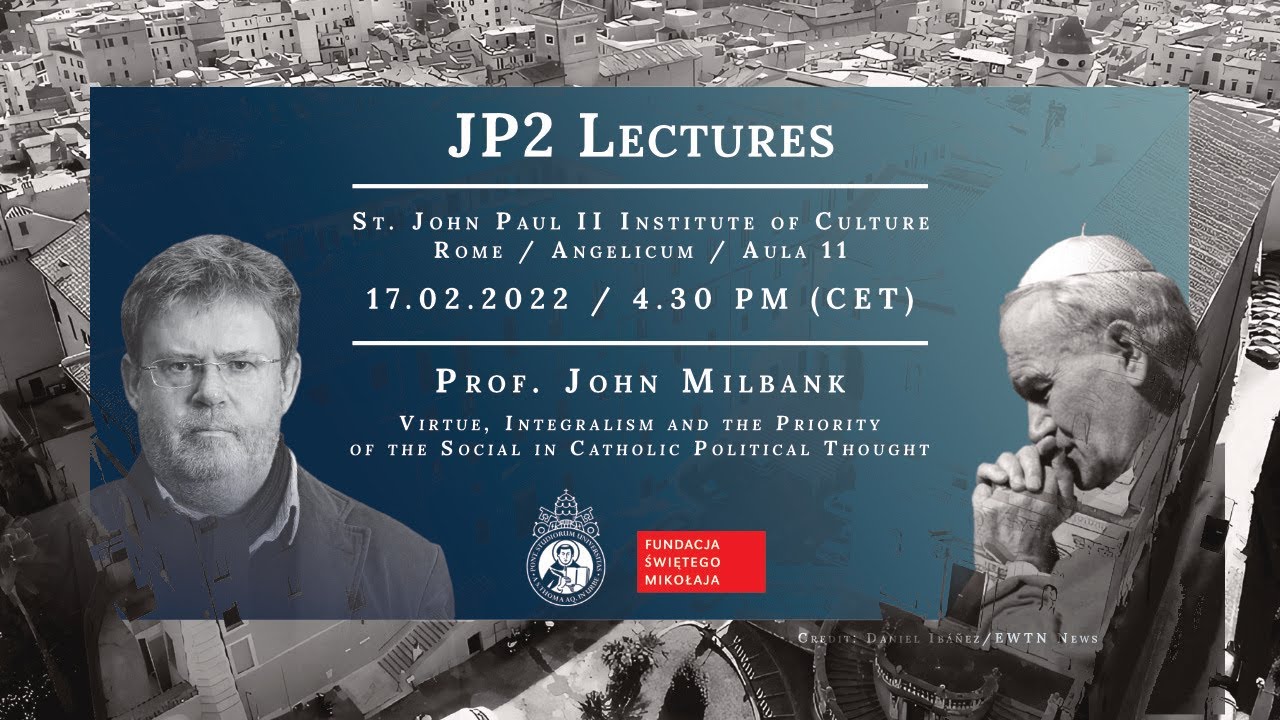

JP2 Lectures // John Milbank: Virtue, Integralism and the Priority of the Social in Catholic Political Thought

February 17, 2022 @ 4:30 pm

On Thursday 17th February 2022 another JP2 Lecture — “Virtue, Integralism and the Priority of the Social in Catholic Political Thought” by prof. John Milbank — was held at the St. John Paul II Instituet of Culture in Rome. For prof. Milbank, the fading of Christian sway caused a loss of solidarity, while the privatization of religious practice did not deliver the flourishing of religion, nor even religious toleration. It is therefore natural to ask whether the triumph of liberal and secular modernity is more actual than we tend to think and whether such a full triumph is acceptable for Christians. If liberal democracy now seems favourable for perverse Sadeian views on sex, gender, life, death, pleasure, and transactions, can we really be sure that the embrace of liberal democracy by Catholicism was altogether a good thing?

The subject was introduced to both in-person audience and online listeners by the Program Director of the St. John Paul II Institute of Culture and the President of Saint Nicholas Foundation, dr Dariusz Karlowicz.

To begin his speech, prof. John Milbank noticed that there is a renewed and ongoing historical debate about the political influence of Catholicism in modern times, as well as about the exact meaning of contemporary catholic social teaching. That debate concerns the way in which the Catholic Church supposedly reconciled itself with liberal democracy during XIX and XX centuries, and whether such reconciliation is theologically acceptable.

For Milbank, the fading of Christian sway caused a loss of solidarity, while the privatization of religious practice did not deliver the flourishing of religion, nor even religious toleration. It is therefore natural to ask whether the triumph of liberal and secular modernity is more actual than we tend to think and whether such a full triumph is acceptable for Christians. If liberal democracy now seems favourable for perverse Sadeian views on sex, gender, life, death, pleasure, and transactions, can we really be sure that the embrace of liberal democracy by Catholicism was altogether a good thing?

Milbank argued that precisely for those reasons we can witness a return of catholic integralism today. He pointed out that “right integralism” is characterized by the conviction that the Church has ultimate jurisdiction over secular matters, without the separation of Church and state and with the relative lack of rights for proponents or religious errors. The integralists are still opposed by those Christians who accept a full autonomy of the public sphere, the total separation of Church and state, and who understand religious freedom as the individual conscience’s right to liberty of opinion. The “right integralism” is not only susceptible to theocracy, by reducing authority to power. It also runs the risk of baptizing purely secular and immanent ways of doing politics, as long as it does not interfere with Christian power, given that, from this perspective, natural law can be deduced and specified independently of the gospel.

By “left integralism” Milbank means not a politically left-wing version of the standard integralism, but an attempt to try to steer a middle course between the twin dangers of excessive eschatological reserve on the one hand, and an excessive emphasis of incarnation on the other. This attempt involves a denial of pure nature, and therefore an integrated account of nature and grace. In that sense, for Milbank, this version of integralism is much more theoretically consistent, and yet, for that very reason, promising rather than dangerous. According to both the Dominicans and the Jesuits of the nouvelle théologie, there is no good reason to despair of the world as the world, because it could not exist, were it not everywhere touched by grace, often in an obscure way; indeed, even the proponents of pure nature, such as cardinal Cajetan, never denied that. There are approaches to charity always and everywhere, and worrying for “anonymous Christianity” in that respect is trying to be wiser than Jesus or Augustine. Nothing in this view threatens the obvious truth, that only the Gospels show God in Himself as friendship and communion, equally emphasizing that the only way to unity with God and human solidarity is through a Eucharistic communion of charity.

In the following part of his lecture, Milbank argued that we can reject the thesis that catholic Christianity is especially favorable to the current model of liberal democracy. Perhaps Catholicism does not reject democracy, since it happily supports majority consent, freedom of conscience, and freedom of individual choice. However, catholic social teaching in its entirety, exactly because of promoting “the social”, implies that liberal democracy can never be sufficient to establish political legitimacy.

Next, Milbank indicated that Christianity cannot consider liberal democracy as a political model that is sufficient and favorable for religion, because by definition it detaches politics from virtue, which Christianity necessarily demands of it. The traditional commitment to a mixed form of government and universal household citizenship, based on the reinterpretation of virtue as charity, has been reinforced in modern times by a new conception of the link of these commitments to the primacy of the social over the political and the economic, even though the social is understood as embracing and connecting these two orders because it is in itself both a legal and temporary order. For these reasons, there is a natural kinship between catholic social teaching both with socialism and with sociology.

To conclude Milbank emphasized that Catholics never gave in to the ways and practices f liber democracy, nor should they do so. Any partial surrender has usually been due to the same dualist and defensive reasons that people sometimes surrender to totalitarianism. Today it becomes again clear, as it was in the Nineteen-Thirties, that liberal democracy is neither stable in itself, nor is it a defense against totalitarianism, but is rather its technical laboratory. Catholic social thought has always known that implicitly, exactly by asserting the primacy of the social. The time has come to proclaim openly that it is also a political theology of the rightful prevailing of the personal, of gift-exchange, and the only one that shapes virtue, which is simultaneously paternal and fraternal charity.

The text of the lecture is available to read here: John Milbank_JP2 Lecture_Left Integralism