An interview with Dariusz Karlowicz, St.John Paul II Program Director and president of the Saint Nicholas Foundation, philosopher.

by Jacek Chelchowski, August 2022

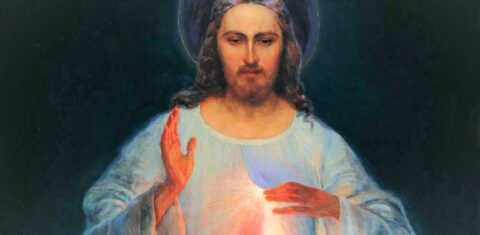

Jacek Chelchowski: Saint Nicholas Foundation and the Angelicum’s St. John Paul II Institute of Culture in Rome invited outstanding Polish artists to paint new versions of the Divine Mercy. Why did you take up painting and sacred painting at that?

Dariusz Karlowicz: The problem that requires attention is the crisis of the great tradition of Catholic religious painting. For the first time in centuries, the truths of the faith are not speaking to the faithful in the contemporary language of imagery. Loud art either does not address Christian doctrine and life or is overtly anti-Christian. There is no point looking for great religious themes in galleries or churches because they don’t exist. With a few commendable exceptions, they are replaced by reproductions, copies or shams. This is the case not only in Poland but also in many places throughout the world.

Can anything be done about it?

Yes, it certainly can. What will be done is what each subsequent generation has done – you have to repaint Catholicism anew.

What do you mean by this?

A renaissance is necessary. Returning to the great themes of religious painting and sacred art is needed. We must do our part without looking at those who claim that nothing can be changed. We start with the image of the Divine Mercy because it is the authentic centre of modern piety. Our piety. Sacred art is, of course, at the highest level of difficulty – it is not about journalistic charges but Truth and Beauty. And this is only the beginning, but – I am convinced of this – a crucial one. We are taking this matter very seriously. We have invited outstanding artists to work with us. Jaroslaw Modzelewski invited excellent painters with profound accomplishments: Beata Stankiewicz, Ignacy Czwartos, Jacek Dłużewski, Wojciech Głogowski and Krzysztof Klimek. The finest brushes of Poland! But there were also young and lesser-known artists such as Bogna Podbielska, Wincenty Czwartos, Fr. Jacek Hajnos O.P. and Artur Wąsowski. In addition, we invited theologians, philosophers and art historians to join us. Our guide to the Diary of St. Faustina is the eminent expert on the text, Dr Izabela Rutkowska, who has carefully reconstructed the Lord’s guidelines for this extraordinary image. Dr Dorota Lekka, a theologian and art historian, researched the vibrant history of implementing this project and the ongoing disputes surrounding the various outcomes of this project. It is worth adding that philosopher Rev. Prof. Jacek Grzybowski, auxiliary bishop of the Warsaw-Praga diocese, is also working with us on this project.

You said that this is the beginning. And what is next?

We have plans for many years to come. Twenty-one, to be exact. The first year and the starting point is the image of the Divine Mercy. The next twenty are the themes of the successive mysteries of the Holy Rosary. The most significant themes of our spiritual and intellectual tradition are the great themes of Western art.

Ambitious plans.

I said plans, but perhaps it would be better to say dreams. The first step is already behind us, and we are preparing for the second.

Why do you consider the issue of painting, and more broadly of culture, so crucial for the Church?

Indeed, this isn’t a matter of interest for a handful of aesthetes but for the future of Christianity. I have in mind the next generations to whom the works of the great masters no longer speak with their former power. We are focusing on painting, but unfortunately, the same can also be said of other fields of art – film, prose, architecture or poetry. The language of the modern culture increasingly lacks images and words capable of telling, nay, even relating the story of Christ’s death and resurrection. The fact that “The Good News” has not been translated into the language of 21st-century culture has made the message mute or incomprehensible. This is a serious problem – but also a significant challenge. We find ourselves in the situation of the Alexandrian Jews before the Pentateuch was translated into Greek. Expressing Christ’s teachings in the language of the next generation is the responsibility of those who are to pass the truth on to the world. It is our collaboration in the work of Incarnation. For Christianity, culture is not a luxury but the very air it breathes.

Is the divorce of Catholicism and art exclusively a problem for the Church?

Certainly not. And this is the second big problem. Without the sacrum, culture dies, leads nowhere, eats its tail – at best, it turns into journalism or performs a decorative function. Those who do not believe T.S. Eliot should look towards the theology of the ancient Greeks. The ancient myth says that muses are the children of memory and the supreme god. They are the daughters of Mnemosyne and Zeus. This is a very profound thought: the core of culture is the epiphanies of the Deity recorded in memory. Without reference to what transcends us, culture becomes a heap of meaningless souvenirs – it is a memory of insignificant things. It proves powerless, devoid of measure. It does not transform, does not offer the hope of salvation, and does not liberate. Involuntarily it nods toward tragedy, emptiness, loneliness, despair, hatred and boredom.

Why has art left the Church?

There are several reasons for the current state of affairs. One can see the effect of the secular Western culture; one can point to curators, galleries, media and academies reluctant to Christianity. One can also point to the Church – speaking of a new iconoclasm and a kind of Protestantisation of the Catholic imagination. But the key to religious indifference, it seems to me, above all, is the lack of serious reflection on the theology of art and ignorance of the obligation to incorporate Christianity into the language of the new culture. Western art’s awe and extraordinary tenderness for sensual reality grew out of deep meditation on the acts of creation and incarnation. In the West, nature is the subject of art because it is the path leading to the Goal. Such art dies together with faith.

What does it look like in the Polish Church?

The question of whether there is a place for creators of Christian culture within the Catholic Church in Poland today is, unfortunately, almost purely rhetorical. Yes, you can find some beautiful exceptions, such as the church in Międzylesie painted by Mateusz Środoń. In general, however, it looks miserable. If Raphael, Bernini or Bach were looking for work, which diocese would hire them? And yet, the problem is not exclusive to painting. The sense of responsibility for Christian culture, still alive in the 1980s, has evaporated almost without a trace. And let’s not delude ourselves. The problem is not a lack of money. Which diocese could not afford to hire a full-time composer? Which cathedral could not afford a Stations of the Cross painted by a great artist? The problem lies in the importance of these matters, the awareness of one’s own – glorified, by the way, in the Council documents – responsibilities, and, finally, the belief that something can be done.

What is missing for Christian art to arise?

Let’s try to look at this problem through the eyes of artists. For simplicity’s sake, let’s leave out those who don’t want to create works containing religious themes. What does it take to create art, the absence of which so troubles us? Three things spring to mind. First, the need for knowledge goes well beyond the workshop of a modern fine arts academy graduate. Second, an environment suitable for spiritual and artistic formation. Third, a market – and therefore patronage, commissions, exhibitions, awards, scholarships. The works of art that still mesmerize us with their beauty and depth to this day could have been created because their creators not only knew how to paint them but also because they received commissions. They allowed them to live, support their families, grow and create more artwork – in a word; they made it possible to practice art treated not as a hobby but as a profession. Patronage, but wise and responsible patronage, is of the utmost importance. Art needs talent and intelligence – but it also requires a sponsor. No commissions, no art.

But artworks are commissioned nonetheless.

Yes! It does happen, but very rarely – once every ten years! Let’s be honest, it is a lack of imagination. Regular, decent income is not a fad. The habit of an occasional commission is more about the hygiene of conscience than patronage. This approach does not give any chance to devote oneself to sacred art seriously. To take responsibility for Catholic culture also means to take responsibility for its creators. Without a profound rethinking of what serious Church patronage should be, change will not happen.

What do you need to do to make this happen?

I don’t have a ready-made recipe. Indeed, a “ferment” is necessary to restore faith in the possibility and awareness of the necessity of a renaissance of Catholic art. It seems to me that this awareness is alive in the minds of many artists today and is being vigorously discussed in circles similar to those of the St. Nicholas Foundation, Political Theology and the St. John Paul II Institute of Culture at the Angelicum in Rome. It certainly needs to be discussed, and action needs to be taken. We start with painting. It is not only about its remarkable past but also about the role it continues to play in the worship and spiritual life of the Church. We would like to give an opportunity to create works of art that wouldn’t be created otherwise. We would like to invite the best, organize workshops and exhibitions, and look for pastors and sponsors ready to work with us. We will see if this works.

Where do you look for money? Are you supported by the Church or the state in this activity?

This venture, like the St. John Paul II Institute of Culture at the Angelicum in Rome, which we founded, is entirely financed by private sponsors from Poland – good friends of the St. Nicholas Foundation and Political Theology. If I may take this opportunity, I would like to thank them very much for their momentum, generosity and selflessness. They are Danuta and Krzysztof Domarecki, Jolanta and Mirosław Gruszka, Wojciech Piasecki, Dorota and Tomasz Zdziebkowski – this couldn’t have happened without them. But of course, this is not a closed club. I ask everyone who believes in this project to generously help us, and thank you very much in advance.

But does modern sacred art have any chance of finding its way into churches? What do bishops, pastors, and the faithful think about it?

Even if something seems difficult, it’s worth trying. I had heard so many times that outstanding artists would never want to take such commissions, so I was stunned when it turned out that truly extraordinary painters wanted to paint the Merciful Christ.

Today I know – and I can say with satisfaction – that the story about the clergy shying away from art is nonsense. Currently, seven of the ten paintings of the Divine Mercy have been commissioned by the pastors of the Warsaw-Praga diocese. A diocese, it should be added, whose bishops – Bishop Ordinary Romuald Kaminski and Auxiliary Bishop Jacek Grzybowski – fully support our efforts. These paintings will soon be in places of worship! Bishop Jacek Grzybowski, the parish priests, the Rev. Krzysztof Cyliński, the Rev. Witold Gajda, the Rev. Andrzej Kuflikowski, the Rev. Ryszard Ladziński, the Rev. Dariusz Marczak, Rev. Emil Owczarek, the Rev. Marek Twarowski, the Rev. Krzysztof Ukleja and the Rev. Sławomir Żarski have pledged to purchase the paintings. What will happen next? I don’t know, but the beginning looks very promising. Excellent artists and courageous, highly imaginative clergy can make the Warsaw-Praga diocese – famous for the works of Nowosielski and Środoń – a major centre of the renaissance of contemporary sacred art in Poland.