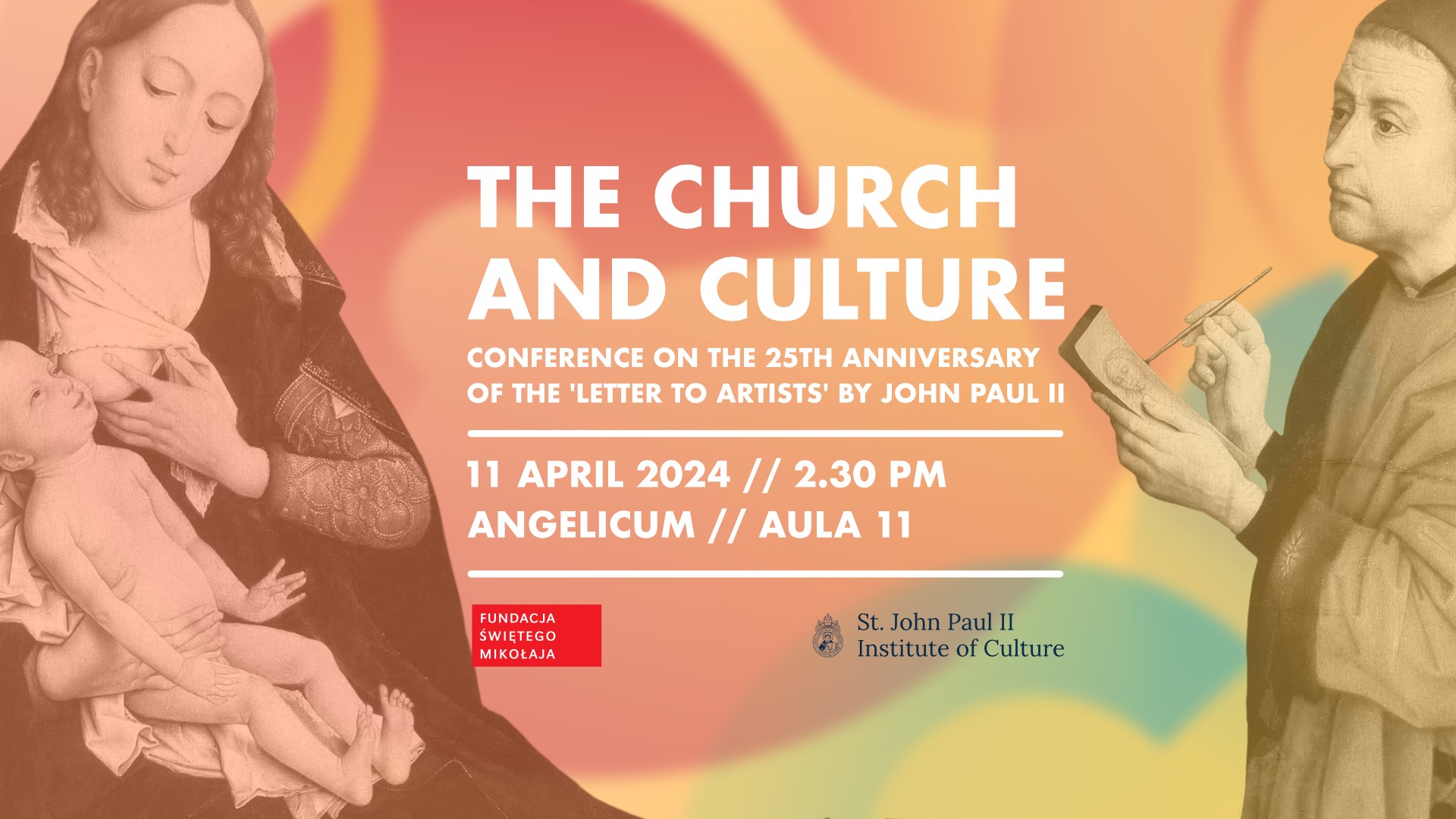

Fr. Cezary Binkiewicz OP, director of the St. John Paul II Institute of Culture, welcomed the audience gathered in the room and behind their screens to then give the floor to the first speaker of the conference: Fr. Prof. Michał Paluch OP, theologian specializing in fundamental theology and eschatology, who delivered the lecture entitled “Proclaiming Redemption with Ingenuity. Introduction to John Paul II’s Letter to Artists (1999).”

Fr. Paluch began his talk by citing the words of Polish Nobel Prize winner Czesław Miłosz (1911-2004), who had commented on the publication of the Letter as follows: It was “an unexpected, delightful, wonderful event. At the very end of a century of horrific wars and crimes (…) a wise and calm voice rang out, reminding us all of what has always been the purpose and vocation of art.” Czesław Miłosz was an artist of the same generation as John Paul II and shared many common experiences with him. In his artistic work, Miłosz dealt with the tragedy of World War II and the struggle against communist ideology.

Fr. Paluch observed, however, that in contrast to Miłosz’s admiration for the 1999 Letter, the reception of this text 25 years after its publication is somewhat different. He explained this through an anecdote: During Fr. Paluch’s studies in Krakow in the early 1990s, a group of Dominican students he was a member of organized a summer theological seminar with Christoph Schönborn as their guest, who was at that time auxiliary bishop of Vienna and chair of a team working on the new edition of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. The young Dominicans conducted an extensive interview with the special guest which was then submitted for publication in a weekly newspaper. After a few days, however, they received a phone call about the text and were asked a rhetorical question: “Is Christoph Schönborn in fact a bishop? How can he talk in such a naive way, as if he was a novice?” After initial consternation, Fr. Paluch then responded to these questions as follows: “This is what is so special about him! Even though he is a bishop, he has been able to retain the freshness of a novice’s perspective.” In the end, the interview with abp. Schönborn was published in its original form.

What brought this past experience to Fr. Paluch’s mind again was his recent rereading of the Letter to Artists. He claimed that in response to John Paul II’s message to artists – written in a very optimistic, even uncritical tone – we could be tempted to ask similar questions: “Holy Father, don’t you see the art that sorrounds us today? When was the last time you visited a renowned contemporary art gallery? Don’t you see how much has changed in recent decades? Don’t you see that art has become an empty play of forms stripped of meaning and any metaphysical ambitions?”

Fr. Paluch’s reaction to John Paul II’s words after rereading the Letter to Artists was similar, which he decided to share with the conference participants in order to further emphasize the fact that we cannot simply and blindly repeat John Paul II’s words without reference to what lies before us. Rather, we have to learn to think with John Paul II about the world we live in today.

In his presentation, Fr. Michał Paluch focused on the search for the conceptual core of the document by recalling the opening words of the Letter from Genesis: “God saw all that he had made, and it was very good.” (Genesis 1:31) Since man was created in the image and the likeness of God, thinking about this likeness is necessary for being an artist. In this light, artistic activity is an imitation of the Creator Himself. However, Fr. Paluch cautioned that in thinking about dynamic artistic work, one must never forget the gap between God – who brought the world into existence out of nothing – and man, who can only process already existing matter and ideas. Artistic creativity, however, will always be the most perfect form of creation’s coming closer to its Divine origin. In the remainder of the speech, Fr. Paluch focused on offering his comments on the interpretation of the Pope’s Letter to Artists, in order to ultimately demonstrate the importance of this document for the modern artist.

The second lecture was given by one of the most prominent contemporary European thinkers and winner of the Ratzinger Prize, Professor Rémi Brague of the Sorbonne, who began his talk with a question about beauty. Why should it be the subject of our reflection? We are talking about beauty, which should not be limited to pleasant sensory contemplation of the nature around us, the poetry we read or the music we listen to, but beauty that is subject to philosophical meditation. As the philosopher explained, beauty can never be discussed in an autonomous manner, i.e. in isolation from its context, contact and dialogue with other ideas. Beauty is an integral part of a complex structure that is a kind of system of thoughts, elements that are articulated and interacted with by us. In his speech, the philosopher presented a rich history of defining “beauty” throughout the history of philosophy. Then, he showed how the concepts of understanding beauty in force today determine the shape of contemporary art.

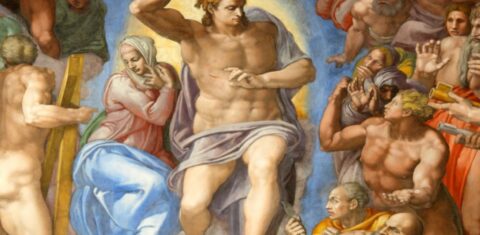

The conference culminated in a discussion led by Michał Kłosowski, which included Cardinal Grzegorz Ryś, Fr. Riccardo Lufrani OP and Fr. Cezary Binkiewicz OP. Cardinal Ryś began by saying that contrary to popular opinion, the Church has not always supported artists. In the early days of Christianity, it was forbidden to be an artist and a Christian, and if one wanted to be a Christian, one could not be an artist, as the art of this period was mostly an act of idolatry. In fact, the earliest examples of Christian art in Rome had been created by pagan artists, not Christian. That is why today, in the Vatican’s ancient necropolis we can see the first painting of Christ depicted as the rising Sun, which was a typical way of presenting the pagan god Helios. It was just a mosaic made by a pagan artist commissioned by a Christian. Cardinal Ryś thus traced the history of this relationship between the Church and artists from the first centuries of Christianity to the modern problems of this relationship.

Referring to the message of the Letter to Artists, Fr. Cezary Binkiewicz OP then undertook a reflection on the social responsibility of art, in which John Paul II saw a never-fading hope on the path of discovering the transcendent. Contemporary art, as the American philosopher Arthur Danto (1024-2013) wrote brilliantly about in his book The Abuse of Beauty, is largely disconnected from the idea of beauty. For the Church, however, the three transcendentals – truth, goodness and beauty – remain indispensable to her relationship with art in the modern world, which urges us not to abandon this hope held by John Paul II. Contemporary artists contemplate the concept of value more than the category of beauty, and it is, after all, a relative idea. Fr. Cezary Blinkiewicz OP also pointed out two key moments for the creation of art: firstly nature, with all its richness, and secondly art as a dream that strives to transform this nature.

Asked about contemporary artists’ expectations of the Church, Fr. Riccardo Lufrani OP gave a sobering answer about the lack of viewing the Church as a place of inspiration and treasury of thought in the perception of modern artists. They do not regard the Church’s heritage as a source from which they can learn. The key problem, therefore, is the disconnection of the Church – which, after all, over the centuries has been not only a giver of norms and values, but also of knowledge – from culture. We are therefore facing a shift in historical reality that we have not yet fully recognized.

In a hierarchical, static society, before the spread of the Industrial Revolution, which dynamized historical reality, society tended to reproduce itself. In that order, religion served as the “salt of the earth” of society. Today – from an ontological perspective – the dynamization of historical reality in the era of exponential technological development is founded on drawing energy from nature and then incorporating it into the machinery of the historical process in which it is processed. The dynamism of changes in historical reality takes place with the simultaneous replacement of the Absolute-God by the pseudo-absolute-man. Fr. Riccardo Lufrani left the conference participants with a reflection on what this dynamization of the historical process and this cultural matrix, in which the entire previous order is turned upside down, brings to man.