Art and Beauty in the Modern World. Account of a lecture given by Rémi Brague

The temptation of idolizing beauty recedes. Some sort of “religion of art” was dreamt of in the late 19th Century among some circles of refined aesthetes, all over Europe. In the present times, such a religion is hardly thinkable. This doesn’t mean that the temptation of idolatry was definitely staved off. On the contrary, other idols replaced art. And I’m afraid they may prove far more cruel and dangerous – notes Prof. Rémi Brague during the lecture given as part of the John Paul II lecture series.

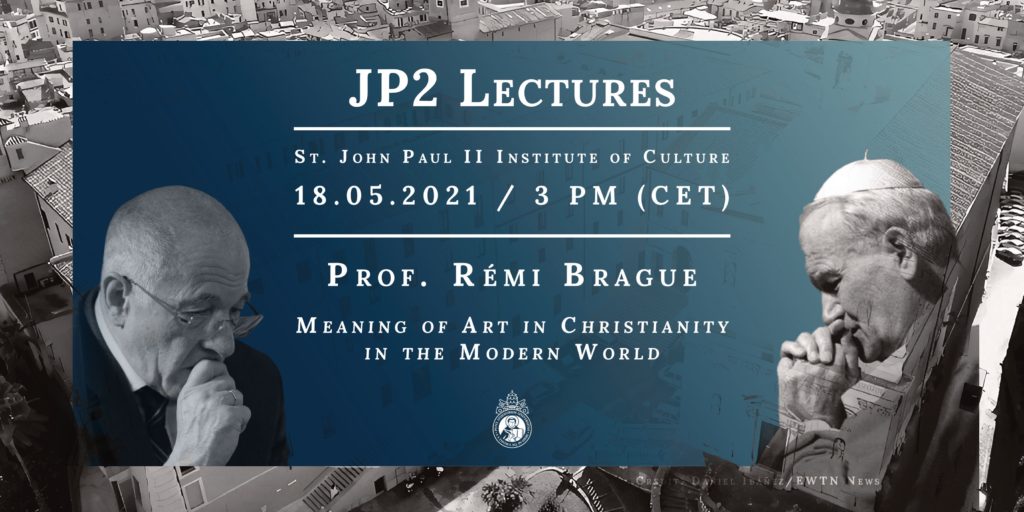

On Tuesday 18th May, the next in our series of lectures held by the St. John Paul II Institute of Culture took place at Angelicum in Rome. The lecture was titled The Meaning of Art in Christianity in the Modern World and was delivered by Prof Rémi Brague, a philosopher and lecturer at Sorbonne and University of Ludwig and Maximilian in Munich.

Rémi Brague’s lecture began with weighing up the many nuances associated with the word ‘modernity’ that is sometimes referred to as the early modern period, and the complications that come with its meaning. History of art has assigned this term alongside the terms ‘contemporary’ and ‘modernism’ as vaguely differentiated at times, moreover these terms overlap in meaning when considering different regions and cultures. But aside from these variances, the early modern period saw a wonderful burgeoning of the fine arts across Europe. In literature, music and painting, new forms and ways of expression allowed for the emulation of what had been inherited from the ancient world. Great craftsmen and likewise artists expanded the limits of artistic expression within their cultures whose underpinnings were to a large extent Christian. The issue for consideration here therefore, is what exactly the relationship between art and Christianity is.

In the ancient world prior to Christianity, the relationship between art and beauty was not defined in a way suited to the notion we have come to know in our contemporary european parlance, that being Fine Arts. Greek philosophers who discerned the ontology of beauty, Plato and Plotinus amongst them, didn’t necessarily identify beauty with artistic production and so their approach could be summarised as seeing art not solely as a means for beauty in itself. It shouldn’t come as a surprise therefore, that by their assigning beauty a privileged position into the realm of ethics, Brague notes how the Greek concept of to kalon would denote aspects associated with nobleness and dignity when rendering the concept rather than beauty in itself, indeed these thinkers were ready to see art production in a lesser light.

Looking for equivalent discernments that we have inherited from the Hebrew Bible when it comes to the issue of how the ancient world understood inspiration, both for artistic production as with prophetic divination, Prof Brague pointed out how we can trace a similitude with Greek thought and Jewish thought. If we take the passage from the biblical book of Genesis as a case in point, the moment where God displays his great satisfaction with the world he creates on the sixth day using the words tow me’od in Hebrew meaning ‘very good’ can also be translated likewise as ‘very beautiful’. This backdrop shows us a plane of agreement between Athens and Jerusalem, a perspective of that which exists being inherently good. And this fundamental premise was naturally embraced by Christianity, summarised Prof Brague.

The contribution which Christianity has made to this evolution Prof Brague describes as revolutionary in its proportions, in that the beauty in the Christian understanding happens to present a paradox. The Passion of Christ as presented by Christian art seeking the highest artistic forms, wouldn’t be comprehended nor would it be accepted by the ancients for the standard of dignity and elevation they required for their status of high art. Torture, agony and humiliation that are depicted alongside with Jesus’s crucifixion do not have place in Classical Greek tragedy or epics. The fact that these qualities happen to be elevated by the Gospel and Apostolic letters makes for a turning point in the development of European culture. This has been noted by the German philosopher Karl Rosenkranz in his work Ästhetik des Häßlichen, where explained is how Christianity introduced a new way of understanding evil and its ways of presenting itself, thereby bringing a kind of ugliness to the world of art while at the same time validating its presence in artistic works.

In keeping with this survey of the largest universal religions, we can see Islam as representing yet another way of perceiving art. Depicting living things in art, according to Muslim doctrine, is seen as the artist usurping the creative competency of the creator, an attempt at recreating his life giving ability. In the Hadith one can also find a clear proscription against this kind of representation in art, but rather directing the artistic production into the domain of ornamental representation from which we get the term ‘arabesque’ in our European languages and likewise calligraphy.

The late modern period brought yet another divergence when it came to understanding art. Just as ancient philosophy allowed for talk of beauty without art, modern thinking allowed for seeing art without beauty. Friedrich Schlegel concluded that the true subject matter of art isn’t that which represents beauty, but rather that which creates interest, in the wider meaning of the word, and furthermore new shocking, grotesque, even sensational elements that startle the viewer. The touchstone, or means for gauging the values art represents becomes the recipient and his reaction to the artwork, where the stronger our reaction the more desirable it becomes. Beauty in its maximal strength here becomes now limited to one of many options for activating this sort of reaction in the viewer. Singularly, where art, commerce and technology meet which would be with design, the role of beauty somehow isn’t infringed. As Raymond Loewy put it la laideur se vend mal meaning ‘ugliness doesn’t sell’.

Art thus, according to this rationale, becomes cut off from its transcendental nature. Even though contemporary philosophers tried to return to the linkage between beauty and truth – perhaps best articulated by Heidegger with his words ‘Schönheit ist eine Weise, wie Wahrheit west’ meaning beauty is the way the truth presents itself, yet this still ends up as no more than truth stripped from its connection to good. The notion of art for art’s sake doesn’t direct our attention to any transcendental truth or reality, but rather towards ‘culture’.

However, the ‘interesting’ parameter mentioned above as an aesthetic category was soon to reach its potential and give way to an opposing conviction. The nineteenth century, particularly the second half, was the epoch of boredom. Boredom was a mutual subject matter for European writers and preeminent thinkers alike, at the time, including Byron, Leopardi, Pushkin, Schopenhauer and Kierkegaard, to name only some. In order to counter the feeling of an encroaching jadedness in culture the dynamic of change in the arts was sped up, seeking new forms for expression, new ways of presentation, and widening limits of the notion of art itself. Somewhat unsuccessfully, as Leopardi noted, in this way change becomes the norm, and this upholds the boredom even more strongly, than a norm without change. And this kind of constant seems to be one upheld to a large degree until today.

Is it possible therefore to hope for a revival or even rebirth of Christian art, in the face of art today which presents such a bleak outlook? According to Prof. Brague, Christian art still has the potential to develop so long as it takes a certain role in relation to the Christian revelations, as it had done over the centuries. When the concept of the ‘artist’ was yet to be defined, which came during the renaissance, art was the domain of craftsmen who worked their craft as best they could and didn’t consider themselves as endowed with a holy-like mission. Their aims were to help the faithful with their prayers, emphasised Prof. Brague.

If art is to overcome the present crises, Brague suggested here, that it does not seem to be possible solely within the boundaries of its own categorical parameters, but rather it needs to be problematised and understood on the backdrop of metaphysics. What is imperative here however, is a return to the transcendentals, those being beauty though also not forgetting about truth and goodness. We are in need of philosophers and saints for a renaissance of art to be once again possible, Brague summarised.

Translated by Tomasz Bieliński